Treating Founder (Chronic Laminitis) without Horseshoes, Section 21

HUMANE HAULING

(Version with full-sized photos)

Hauling horses in trailers is germane to a discussion of founder because hauling with the horses' heads facing forwards can involve so much more muscular exertion than hauling facing rearwards that you can actually trigger laminitis in more vulnerable animals from stress, over-exertion, and the resulting lactic acid buildup.

Other adverse physical effects of the stress of forward-facing hauling, some of which make laminitis more likely:

1. Dehydration--due to sweating from fear, and the muscular exertion to brace to remain standing when the trailer is moving, and an unwillingness to drink in transit. (When I do long hauls, we take breaks every couple of hours, and I ply them with water made more interesting by dissolving lots of peppermints in it, or in truly desperate moments, orange Gatorade in bowls, or even pop, if all else fails.)

2. The stress of trailering leads to abnormal blood values--elevated glucose, cortisol and CPK; lowered calcium and neutrophilia.

3. Impaction colic and choke are more likely when the horse is not drinking, but nervously bolting hay. Colic can trigger laminitis.

4. The "anticipatory propping" position the horse assumes to protect himself causes pain. is much like the "founder stance," with the feet far out ahead of the horse, and involves much exertion, because it is abnormal. This tense, high-headed stance also results in back strain and cramped back muscles, sore shoulders, etc.

5. The stress of transit can result in weight loss, tying up, and aggravate latent infections.

6. Mares in estrus can go out during the stress of a trailer ride.

7. Horses being backed out of a trailer, operating blind, can hurt themselves and their handlers.

We cannot emphasize enough how much can go wrong transporting horses! Here is a link to a Power Point presentation given by Dr. Sharon Cregier at the 2015 Animal Transportation Association's conference, containing many photos of trailer wrecks, with comments on why they occurred, and what we can do to make transporting horses safer. This is a large file size: 10.1 MB.

http://www.naturalhorsetrim.com/ATA_2015_Apr_27_Cregier_presentation.odp

Some of these photos are from Dr. Rebecca Gimenez of Technical Large Animal Emergency Rescue, Inc. More information on their work, and a book about it: http://www.tlaer.org/

Dr. Cregier and Dr. Gimenez are campaigning for improved standards for non-commercial horse trailers in Canada. Here is a link for this file: http://www.naturalhorsetrim.com/Non_Commercial_Horse_Transport_FINISv1.pdf This is a large file size: 14.8 MB This document contains many more photos of what can go wrong hauling horses, and proposed solutions to improve safety.

Range Rover has come out with a system that monitors traffic behind the trailer, and conditions inside the trailer, including live video, temperature, vibration, etc. They also have a "transparent trailer" system that lets you see in a rear-view mirror-shaped monitor what is behind a trailer--no more blind spots. Inside the trailer can be monitored remotely by your smart phone, too. This is an amazing system! You can monitor what's going on in the trailer either in the vehicle's cab, or on your smart phone. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9HmdIh6AYw

Click here to see a spectacular case of a horse panicking in a trailer

(Photos from the Columbus Dispatch.)

PHOTOS AND MORE INFO about a spectacular semi trailer wreck (carrying 59 horses)

(Photos from the Kenosha News, and rescue workers, (Oct. 30, 2007)

...We need to take their fears SERIOUSLY!!!

I began to wonder why my horse, who had loaded readily when I first got him, became more and more reluctant to load. I began to wonder why he was breaking butt chains, and rubbing his tail raw on the back window bars of the conventional, forward-facing 2-horse trailers I used with him. His former owner had always hauled him loose in a well-bedded, big open stock trailer, and had none of these problems. I began to wonder why he would not urinate in transit--on longer trips, he would not do it unless I unloaded him and took him into deep grass....and then he did not want to get back in again. I saw horses where I boarded being unloaded, flying off trailers like rockets, covered with sweat and lather, and trembling in fear. And these same horses would not get in willingly.

I began to search for answers. Fortunately, I stumbled onto the work of Dr. Sharon Cregier. I saw an article she wrote in Equus Magazine, which put me onto her work. I obtained a copy of her PhD. thesis, "Alleviating Surface Transit Stress on Horses," from University Microfilms, 300 N. Zeeb Rd., Ann Arbor, MI 48106. Unfortunately, it is no longer available there. However, I have uploaded files for her presentation to the 2015 Animal Transportation Association conference, and a document proposing safety standards for non-commercial horse trailers in Canada. These represent her more recent work, anyway.

http://www.naturalhorsetrim.com/ATA_2015_Apr_27_Cregier_presentation.odp This is a large file size: 10.1 MB

http://www.naturalhorsetrim.com/Non_Commercial_Horse_Transport_FINISv1.pdf This is a large file size: 14.8 MB

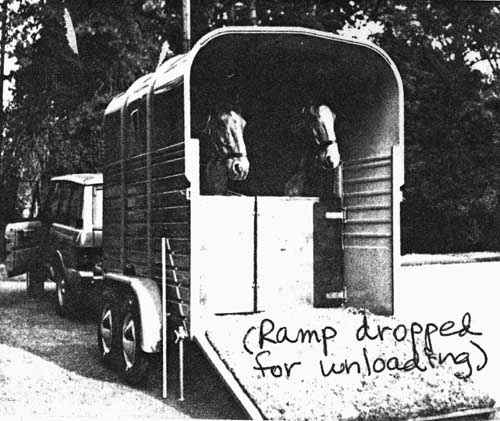

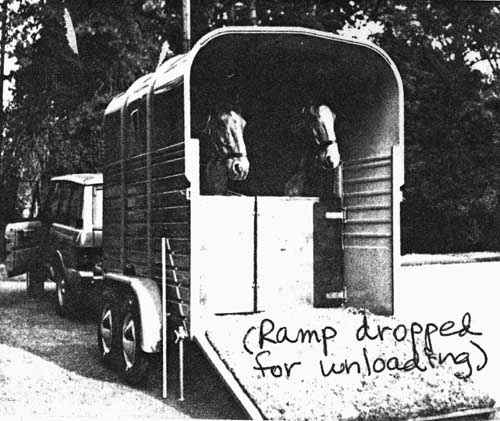

One of the main points of Dr. Cregier's thesis was that having the horses standing facing rearwards had numerous benefits. Below is a "Kiwi Safety Trailer," originally designed by David Holmes in New Zealand. It was the only 2-horse bumper hitch trailer that can pass NZ's trailer safety standard of being able to bring the vehicle to a panic stop within 30' at 20 mph without jack-knifing or knocking the horses off their feet.

The late, lamented "Kiwi" trailer made by Rice Trailers in the UK.

I WISH they started making them again!

However, David Holmes' daughter, Odessa Holmes, has carried on and designed a more luxurious version of the rear face trailer: www.equibalance.co.nz A great deal of care has gone into getting this trailer balanced, and it is more durable than the original Kiwi trailer. These trailers are only available by special order.

For 2-horse rear-face KIWI TRAILER SKETCHES AND APPROXIMATE MEASUREMENTS, Click HERE

In a letter to me, Sharon wrote: "Any standard [forward-facing 2-horse] trailer will throw the horse forward during braking...threatening its head, chest, and balance. Once a horse in the rear face learns that acceleration and deceleration no longer throw him, he drops his head, leans forward and stands very much as he would in his own stable throughout the trailer's journey. He stays in a balanced posture because his center of gravity is directly over that part of the trailer which moves the least [the axles]. During braking in the rear face, the horse's haunches drop a little, his head drops and leans a little further forward over his forehand. That's it. No head throwing. No maintaining an anticipatory propping. No scrambling. If the braking was really hard (for example, a sudden stop against a barrier collision), the horse's buttocks, not his head, would bear the brunt." Further, she said that the quickest change a horse would experience in a trailer was braking. No vehicle can accelerate in nearly as fast a change as strongly applied brakes.

I set out to see for myself if Sharon Cregier's claims were true. I rode in various trailers with horses. It was an eye-opener! Everything Dr. Cregier described, I saw. Only it was worse than she described it! Hearing about something rather bloodlessly called "anticipatory propping" is not the same thing as seeing a terrified horse actually doing it close at hand! I also saw horses in loose invariably turning to face the rear when they had a choice. I saw horses in slant loads trying to turn around in their slanted stalls to face rearward as well. I also saw the danger of the handler leading a horse up into a slant load stall--he was trapped between a wall and a rearing horse at an acute angle and could not escape.

I tried getting down on all fours in trailers, or even in the backs of station wagons or pickup trucks, and found that when I was headed forward, a sudden stop landed me right on my face. When I was facing the rear, however, a sudden stop was easy to absorb by my "hindquarters," which are designed to push me forward, but not hold me back. If worse came to worse, my butt would hit the front bulkhead, which stopped me rather painlessly. It was enough to keep me calm; facing forward, I was always on the alert for the next braking that might throw me on my face. By being on all fours, I do not mean crawling on your knees, which does not fairly replicate the full effect. I mean, stand on the balls of your feet like a horse would, and your hands in the front.

Next, riding with my horse in my standard, forward-facing 2-horse trailer, which I had regrettably bought before I knew better, I saw for myself how and why he was breaking butt chains. He was doing the "anticipatory propping" Dr. Cregier refers to. He was actually standing in a "founder stance," with his front legs far out ahead of him, his hind legs way up under his belly, his head held high in the panic/flight position, and sitting on the butt chain. He was crushing his tail into the door. He was terrified, scrambling and trembling during even "normal" driving. On the turns, he was flinging himself into the center divider, and scrambling. Yet when he got off the trailer, he was not nearly as sweated and lathered as many horses I had seen getting off other trailers. How much more traumatic their rides must have been!

The hind end is not designed to comfortably stand any length of time with the hind feet propped out to the side to provide stability in turns; ligaments are stretched uncomfortably. This is why they teach you in pony club to ask for the hind feet straight out to the back, not held out to the side, when you pick the hooves out. The front end, on the other hand, is much better able to comfortably maintain a wider stance. When the weight is on the forehand, as it can be in a rear-face trailer, the horse is free to balance side to side against the vehicle's turns by leaning into his thoracic sling. Ligaments are not being pulled; the horse's front end is more laterally fluid than their hind end. Dr. Cregier likens the thoracic sling to gimbals.

While riding in the tow vehicle with Odessa Holmes while we were hauling horses in her Equi Balance trailer, we could view the horses over a closed circuit video monitor. (This is a great idea for anybody's trailer, by the way!) I was surprised to see how much more effectively the horses could balance leaning into their thoracic slings, their weight resting naturally on the forehand, to stay balanced while the vehicle was taking turns. Another very important consideration is that they were tethered in a way that would allow for a relaxed, low head carriage. The front-facing horses I rode with earlier were throwing themselves into the center divider, and sometimes scrambling in the corner where the wall and floor met, if turns were taken at speed. A very sturdy divider was needed to support them doing this. In Odessa's trailer, even with turns at some speed, the horses were barely touching the center divider. My initial misgivings that the center divider looked too weak to support them if they would throw themselves into it turned out to be unfounded. Odessa's claim that the center divider could really be dispensed with turned out to be truthful. I admit it was initially a stretch for me to accept this idea until I saw what was actually going on in the trailer. As I watched the video monitor while we drove along, the horses were barely touching the center divider, even during turns. They weren't stomping or scrambling; they stood calmly and quietly, even during turns, and going up and down hills. This was quite a contrast to what I saw riding in trailers with horses facing forwards.

In any event, the sheer physical exertion needed to maintain the anticipatory brace position over a longer haul might be enough stress to trigger laminitis in a susceptible horse. Commercial haulers have been offering rear-facing stalls in their rigs for years. Wentworth Tellington of the Pacific Coast Equestrian Research Farm did a study Dr. Cregier mentions in her thesis. He monitored heart rates of horses hauled first facing forwards, and then rearwards, in the same van; their heart rates were slower, indicating less stress, when facing rearwards. Commercial haulers also know that horses facing rearwards are less tired by traveling. They also have found that horses traveling with their heads free tend to stand facing the rear of the trailer. Further, a horse with his head free is better able to balance and relax.

Dr. Cregier warns you not to try and convert a conventional, forward-facing bumper hitch 2-horse trailer into a rear-face model without moving the axles somewhat forward, enough to reduce the tongue weight of the fully loaded trailer to 100 lbs. max. (on the original Kiwi trailer design, without a dressing room.) If you load the horses rear-facing in a trailer with the axles too far back, the increased tongue weight will result in a rough ride, transmission and engine wear, poor steering and possible jack-knifing during braking. She also notes that the Kiwi trailer could come to a panic stop quicker than other trailers without jack-knifing, etc.

Some advantages of rear-face trailers over forward-facing trailers:

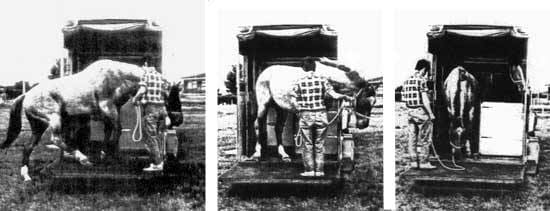

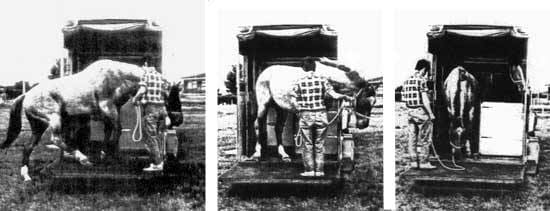

1. Loading and unloading the rear-face trailer are considerably safer and easier than with conventional forward-facing 2-horse trailers because with a rear-face trailer, you lead the horse up onto the ramp, do a turn on the forehand, and back him in. To unload, you just lead him straight out. You are never in his kicking zone, or a blind spot--you remain at his head at all times. You are never trapped between a wall and the horse. You are never leading him into a dark, confined place head-first. He can see where he is going coming out, rather than backing out blind. You aren't driving him from behind in his blind zone. You aren't in the blind spot/kicking zone to fasten the butt chains.

Teaching a horse to load this way: Earlier, people were using a wall, or a wall of hay bales, as a training aid to teach a horse how to load in this fashion. What Odessa Holmes advised us now is that they have gotten good results without this step. They first walk a horse across ramp while it is still dropped down to the ground--onto the left side, and on over to the right side--to get him used to stepping onto the ramp.

Next, they get him to halt quietly on it.

Later, the ramp is raised by its supports into the level loading platform position, both front and rear ends of the ramp supported to make it feel more stable. You get him to step up onto it, and later, to stop on it. It is a short step from there to get him to turn on the forehand and then back into the trailer. Leaving the center divider over to the side in the earlier stages of teaching this makes backing into the trailer easier and less of a precision operation.

Loading a "Kiwi" trailer--the handler is never trapped

between a horse and a solid wall!

(To unload, the horse walks straight out, and is less

apprehensive because he can see where he is going.)

2. The "anticipatory propping" stance (weight shifting back, and fore legs propped out in front) that a horse assumes in forward-facing trailers to be ready for the next gear shifting or brake application is exhausting and stressful. Horses traveling facing backwards are able to settle in and assume a more relaxed stance with their weight more naturally on the forehand. Anticipatory bracing in forward-facing trailers also discourages male horses from urination, which requires parking out on the forehand, the opposite of the propped stance that is so much like the founder stance.

3. Sudden braking is less of a problem with rear-facing trailers in terms of injury to the horse being less likely. I will never forget suddenly braking a forward-facing Thoroughbred walk-through; the horse fell and was trapped under the breast bar. If I had not stopped and freed her, but just gone on a few more hours, she might have struggled and panicked so much that I would have had a dead horse. She was already getting shocky in just a few minutes of being trapped under the breast bar.

The cattle industry refers to the weight loss of transported animals as "shrink," which can be a considerable percentage. The stress of trailering, particularly in forward-facing trailers, has been shown to cause a loss of weight, increased susceptibility to infectious disease, and result in abnormal blood values--leucocystosis, decreased calcium, and elevated cortisol, glucose and creatnine. These blood value changes all testify to the great physical effort required of the horse during conventional transport. Until you have actually ridden in trailers with horses, you have no idea what it is like for them!

Considerate driving is also key. Driving that many feel "normal" is usually too fast, jerky and abrupt for an animal trying to remain balanced on his feet in the trailer. Having one person riding in the trailer with the horse, in touch with the driver via cell phone, can be very instructive. I was told by one such person that it felt like my trailer was "going 100 mph" when we exceeded 50 mph. I never could have known that, sitting in the cab, without getting some feedback from the trailer. I have been really frustrated with how much resistance I have run into on the subject of riding in trailers with horses, though. Most people think they're doing fine if they get the horses somewhere in one piece, and aren't the least bit curious about WHY the horse hates being loaded and hauled. They prefer to see unwillingness to load as strictly a discipline problem, rather than being open to learning first hand how trailering effects the horse.

The bird dog trainer I bought Max from was not being cheap by using an open stock trailer to haul him in, he was being smart! Max would voluntarily stand facing rearwards, slightly diagonal, and directly over the axles, where the ride was at its most stable. He was able to park out to urinate en route in the bedding. He could see what was going on. He was a lot calmer. He went in more readily. He walked out in a civilized fashion, not like a shot out of a gun, as he did later in conventional 2-horse trailers.

By the way, Dr. Cregier thinks torsion bar axles are highly desirable.

My personal experience, too, is that gooseneck trailers have vastly improved handling, ride and maneuverability over bumper hitch trailers. Sorry I didn't get one!

Also, Dr. Cregier recommends a shock-absorbing hitch. More info: http://www.overtons.com/modperl/product/details.cgi?i=25107&pdesc=Tie_Down_Ball_Breaker_Shock_Absorbing_Hitch&str=breaker&merchID=1008&r=view

This rubber torsion my be too light duty for some trailers, but here is a description: "Tie Down Ball Breaker™ Shock Absorbing Hitch-The Ball Breaker Hitch reduces wear on your drive train and greatly reduces driver fatigue. Rubber heavy-duty torsion shocks with progressive compression absorb push-and-pull horizontal shocks as well as vertical shocks to your trailer and tow vehicle. Fits standard 2" receivers. 500-lb. tongue weight. Class 2."

We need to do everything we can to reduce transit stress in horses, especially in dealing with horses who are more prone to laminitis. Transit stress can actually trigger laminitis in more vulnerable animals.

To get a copy of Sharon Cregier's PhD. thesis on reducing transit stress in horses, contact University Microfilms Information Service in Ann Arbor, MI: 800-521-0600 or 734-761-4700. Costs, when I last checked, for students ordering soft cover thesis copies is $40; for non-students, $59. This thesis has an extensive bibliography of other research. There are also many good articles on the AATA web site: www.aata-animaltransport.org

For more information on rescue techniques in trailering wrecks, here is an article that appeared in The Mail Tribune, a newspaper published in S. Oregon:

|

November 5, 2006

|

John Fox, left, Deb Fox and Angela Gonzalez demonstrate how to roll a horse over using a strap on a horse manikin. (Mail Tribune / Jim Craven) John Fox, left, Deb Fox and Angela Gonzalez demonstrate how to roll a horse over using a strap on a horse manikin. (Mail Tribune / Jim Craven)

|

The horse rescuers

Couple teaches emergency techniques for large animals; local organizations hope to launch rescue team

By Meg Landers

Mail Tribune

If Cris Usher and some of the other responders had had large-animal rescue training a year earlier, a horse that was stuck might still be around.

"Last year, the Applegate Fire District had a situation where a horse was in a pond," said Usher, of Applegate Fire District 9, the Josephine County Sheriff's Posse and Josephine County Equestrian Coalition. She said no one knew what to do and techniques she learned Saturday would have come in handy. "The horse ... did not make it."

There's no system in place to prevent the scene from happening again.

"Right now we can't expect to call 9-1-1 and have people respond," to a large-animal emergency, she said.

Usher is among the participants in a two-day large animal rescue clinic held Saturday and today. Local organizers hope to put together a team of responders in Jackson and Josephine counties.

Firefighters from Ashland and Grants Pass as well as California fire districts are attending the clinic held at Eden Farm in Ashland, as are employees of Josephine County Animal Control and local horse owners. The clinic is sponsored by the Josephine County Equestrian Coalition.

John and Deb Fox, firefighter volunteers with the Felton, Calif., Fire Protection District, have developed a training curriculum and manual on large-animal rescue techniques.

John Fox said he looked nationwide for information on equipment firefighters needed to rescue large animals and found nothing, so 12 years ago he and his wife took the initiative. Whether animals are trapped in a trailer wreck, a ditch, the mud, a lake or river, a ravine, a collapsed barn or a show ring, the clinic teaches skills to assist in saving them.

From making a rescue strap and strapping it around a horse's girth to flipping over a 450-pound recumbent manikin, the Foxes demonstrated numerous techniques, often done with standard fire engine equipment such as hoses, utility ropes and pike poles.

A large part of the clinic involves education on anatomy and behavior of a horse, said Deb Fox.

"Firefighters have a tendency to rush in," she said. "That doesn't work with these guys."

The Foxes also taught tips on how to stay out of danger, such as how to organize the ropes so they don't become entangled around the rescuer's legs, which would pose a risk if the horse suddenly took off. They also suggest rescuers keep their mouths closed and teeth together to avoid biting off their tongue should the horse suddenly jerk.

Jannalee Smithey, president of the Equamore Foundation, a nonprofit rescue organization in Ashland, is among the clinic organizers.

"We are forming a committee for equine rescue solutions," she said. In addition to encouraging firefighter and law enforcement training, she hopes to create a list of citizens available to help because rescues can require a large team of people.

The techniques can apply to cows, llamas and pigs, too.

"It's almost always horses," said John Fox, adding that for many people a horse is more like a family member, and owners may put more effort into trying to save it.

For more information or to get involved in large animal rescue in Jackson and Josephine counties, call Jannalee Smithey, 535-6607.

Reach reporter Meg Landers at 776-4481 or at mlanders@mailtribune.com

|

Back to home page--Table of Contents

Article in sections with "thumbnail" photos for fastest downloads:

1 9 17

2 10 18

3 11 19

4 12 20

5 13 21

6 14 22

7 15 23

8 16 24

NAVICULAR

Article in sections with full-sized photos for print-outs:

1 9 17

2 10 18

3 11 19

4 12 20

5 13 21

6 14 22

7 15 23

8 16 24

NAVICULAR

To Strasser case studies--thumbnail photos for faster downloads

To Strasser case studies--large photos

Please sign my guest book! Photos of my pets My farm

Share Barefoot success stories on this page

Buy or sell used HORSE BOOTS Natural board Barn Listings

Click here to subscribe to naturalhorsetrim

(I moderate this listserv to weed out "fluff.")

Send Email to Gretchen Fathauer, or call (740) 674-4492

Copyright by Gretchen Fathauer, 2015. All rights reserved.